7 October – 2024 (Index Treasure) This story has a new photo and headline.

Nour Swirki knows only one thing: she must escape.

But for different reasons, she can’t do it. Sometimes, it’s because the car meant to whisk her to safety − away from Gaza to her children in Egypt − won’t start. Sometimes, her bags are too heavy to carry.

Crowds sometimes stop her. Often, she doesn’t understand why she can’t leave.

As of Monday, it’s been a year of fighting in Gaza between Israel and Hamas. It is a result of Hamas’s Oct. 7 attacks. They killed 1,200 in Israel and kidnapped 251, taking them to the Palestinian enclave. Since the war began, over 41,000 people in Gaza have died, says the Hamas-run health ministry.

Much in Gaza, besides lives, has lost. Entire families, neighborhoods, and a rich cultural heritage are gone. This includes mosques and libraries. The war has changed the Middle East. Hamas has decimated its leadership. But, a cease-fire is still out of reach. The war may spark a wider conflict with Iran and Hamas’ allies in Lebanon and Yemen. It’s ushered in fresh scrutiny of the decades-old plight of Palestinians. It has brought tragedy and trauma to Israel but also isolated it on the world stage. The war could impact the U.S. election.

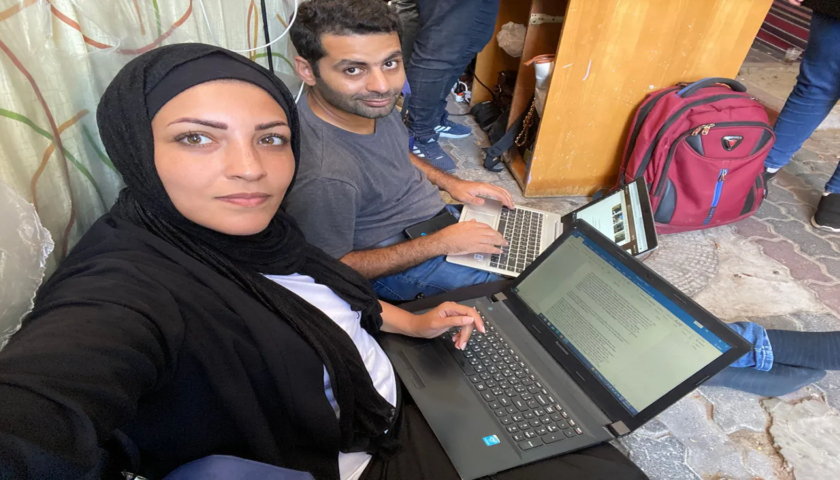

For Swirki, 36, a Palestinian TV journalist, it’s been a year of nightmares about never escaping Gaza. She’s been trying to survive while doing her job. As of late September, at least 116 journalists cannot do that, says the Committee to Protect Journalists.

“My dreams are all about evacuating because this is my real-life nightmare,” Swirki said.

As the war has dragged on, time for Swirki has become indistinct. It’s become harder for her to understand or even think about the devastation of the past year. Many of the people and things she knew, many of the streets she knew, are no longer there to see or touch. There have been too many losses and separations for her to make sense of.

As the war hits its one-year mark, two separations weigh on her. They hold a promise.

Their names are Jamal, 11, and Alia, 13. Her children. She and her husband, Salem, also a journalist in Gaza, evacuated their kids to Cairo in April, where they are staying with their mother’s sister and parents.

The family of four has not been together since. In her darker moments, Swirki wonders if they ever will. “I am relieved they are in a safe place. I miss them so much,” she said. “I just want to survive to meet them again.”

One year in Gaza, four times displaced

In Gaza, the experiences of the Swirki family over the past 12 months are not atypical.

They are among almost 2 million Gazans. The UN reports that 9 of 10 people have displaced at least once since Oct. 7, 2023.

An Israeli airstrike destroyed their house in Gaza City. They have fled for safer shelter four times. Like most Gazans, they lack access to food, water, sanitation, and health care.

They have seen family, friends, and colleagues killed. They had little time or space to grieve.

A week before Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7, Nour Swirki posted on Facebook. She found it funny. Her son was making short videos about soccer results instead of studying for his math exam.

A year later, Swirki wrote on the same platform, “Every morning I wake up here the shock still hits me.”

“I’m thinking about how life passes in parallel worlds far away. One can only witness it, not be present in it.” Things and time pass without meaning, without purpose,” she writes.

In Rafah, in southern Gaza near the Egypt border, the family escaped the misery of living in a tent. The camps stretch for miles and spill into empty or destroyed fields, streets, and lots.

But the shelter they were in didn’t provide any extra comforts.

No one felt safe.

Jamal and Alia Swirki spent much of their day searching for firewood for cooking or standing in line for water.

Studying was impossible. Few books existed. Internet and cellphone service were unreliable.

Both children eventually contracted hepatitis, caused by drinking water contaminated with raw sewage.

Swirki described Rafah as lacking infrastructure and places to go. “Our clothes were dirty. We had no way to wash them. It was very tough for me as a mother,” she said.

In February and March, it became clear that Israel was prepping an all-out offensive on Rafah. This was part of its efforts to hunt and defeat Hamas and free its hostages.

Israel’s military had already launched airstrikes on Rafah. Palestinians sheltering there saw them as largely indiscriminate. But, Israel disputed this. On Feb. 12, over 100 people died in Rafah, say aid groups. Some media called the airstrikes the “Super Bowl Massacre” because they coincided with the Super Bowl.

“The children’s mental health was declining. They were losing weight and begged us to move them to a safer place,” Swirki said. “The bombing and shelling were too much for them.”

For the Swirkis, deciding to send their kids to Cairo was tough. They had debated it for months and were deeply conflicted.

As journalists, they felt obligated to be in the field as much as they could to document the war’s impact on Gaza. Many of their colleagues had paid the highest price − their lives − to do just that. In the last year, journalists in Gaza have repeatedly reported, sometimes live on air, that Israel’s forces have phoned them. The calls warned that they and their families would be targeted for attack. Then the attacks came. Israel strongly disputes any suggestions it is deliberately targeting journalists but the belief that they are is widely shared among Gaza’s journalists.

It had pineapple and orange pieces.

A paper message was attached.

“From Cairo’s displaced to Gaza’s. Happy birthday,” it said.

No candles were there to light or blow out.

Yet, Nour Swirki made a wish. She made two.